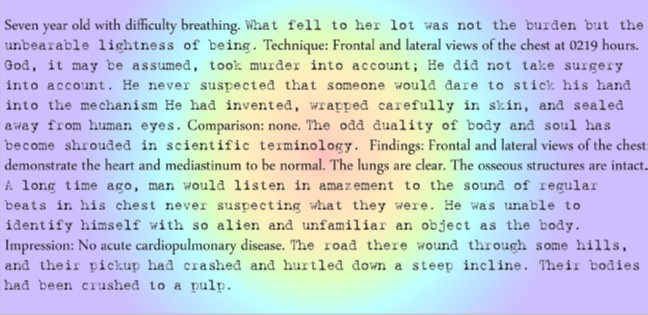

Visual Rhetoric and Love Notes from the Radiology Department:

The Incredible Lightness of Being X-Rayed

From Star Trek to Avatar, medical imaging in sci Fi seeps across the fiction/science blood brain barrier , a thinner line than the frenetic scrawling of an EKG readout. Nearly every medical scene in Sci-Fi eschews numerical data of real world modern medicine for the more cinematically impressing displays of ethereal specters of light hovering above the injured or Ill. Center stage of these scenes is the narrative's medical professional, whether Doctor or medic, who manipulates the glowing overlay of the imagined body or interfaces with a device that, in turn, interacts with the digitized patient.

An inner tension in these scenes stitched with the drama of the injured or Ill character exposes an elusive and covert concept: the inherency of fiction in science, which for this research transplants that drama from an explication of various sci Fi medical imaging scenes to the fictionalized reseeing and retelling of actual medical events, mythically, if not mystically, which with a more penetrating scan seems appropriate for understanding both real and fictionalized medical science. By using our own gaze to examine these complicated and real world medical events as they interlace fictionally, we can expose and lay bare the prose and prosody of medical imaging in science fiction, of the medico-fictional epistemological model.

Medical texts can be decoded with fiction; fiction generates knowledge. In a time when every device speaks—pinging, notifying, telling us what to watch, eat, buy—fiction offers relief from noise. Fiction gives shape to what the data excludes such as the pain and joy of human existence. Fiction offers truth.

I have a short, completely true story to tell. It is about a cryptic love note hidden in a radiology report that unravels the blurred boundaries between medical imaging, existential anxiety, and the stories we impose on clinical data in an age of algorithmic certainty that forgets how to read between the lines. To understand what the scan refused to explicitly state, fiction is conjured like a spell to summon meaning from the shadows, the metadata, and the margins.

If medical intervention feminizes the patient by establishing the physician as a patriarchal figure standing in authority over a passive, dutiful body, then it stands to reason that the relationship between the patient and physician must be one of love; it is the open, sacrificial love of a person offering herself on faith – in the medical credentialing process – to one who will make her whole.

My daughter’s lungs are 27 years old plus as of today. This story starts twenty years ago, one night when my daughter went to bed and began coughing. At midnight, I called her pediatrician.

“She can’t seem to breathe,” I said.

My daughter gasped for air; panicking made it worse. On her physician’s instructions, we went to the Emergency Room, where two kind medical staffers x-rayed her chest after the ER physician administered medication that stemmed her coughing fits. At the time, I registered them as men — and only now, decades later, do I realize I may have mistaken performance for identity. I share this detail with the understanding that memory, like medicine, is fragmentary and flawed.

The x-rays were to determine whether she had bronchitis or some other lung ailment. She didn’t. That night, the hospital experienced receiving a record number of head traumas from motorcycle accidents, moving croup patients down the list of priorities. My daughter and I spent hours in a cold room — no phones to distract us, no apps to diagnose her or conjure AI-generated calm from regurgitated fragments of data scraped from unimaginable sources. Instead, we watched videos of dancing bears on a very small television set. Nevertheless, she left the hospital able to breathe, which fulfilled our goal.

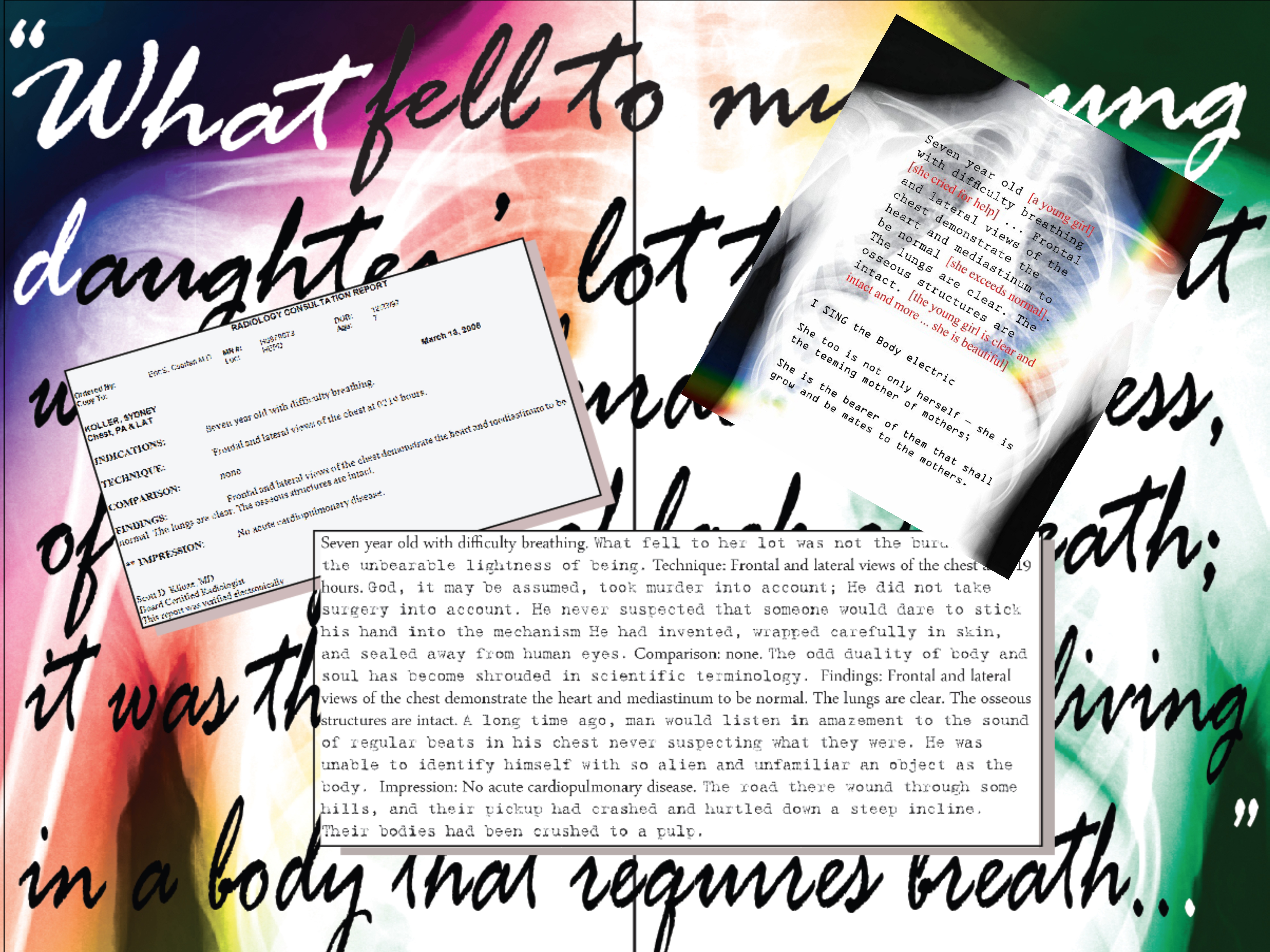

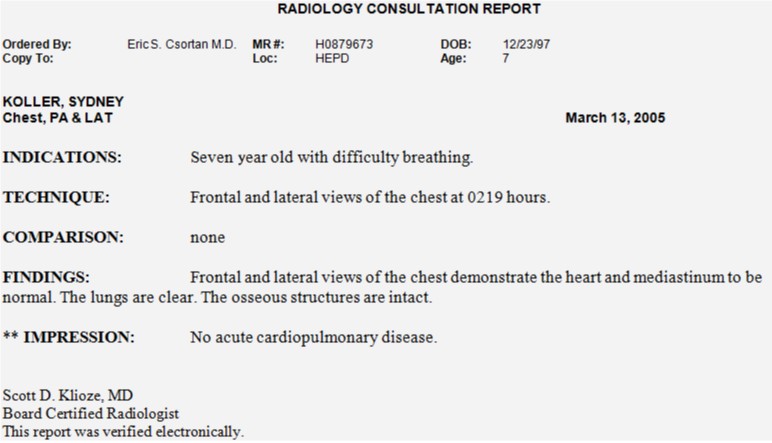

Later, I read the report interpreting my daughter’s x-rays and realized that the radiologist loved her. See image 1 for proof. Upon scrutiny, however, it seemed clear that he was hiding something, as lovers often do. The text – plainly a love note – that bonded my daughter and him, only covertly identified his feelings. I could not decipher his message very easily. His love remained hidden in a way that hurt me. The medical record seemed stripped of meaning; it said nothing of my daughter’s beauty, sense of humor, or love of domesticated animals.

My daughter was more than a “seven year old with difficulty breathing.” Yet I could not ask Dr. Klioze what he meant, because he only existed as a line of metadata. Neither my daughter nor I ever met Dr. Kloize. He appeared merely as a timestamp and sterile assurance that someone or something read the x-rays sometime later that night. The report itself states -- as an autobiography of sorts -- “This report was verified electronically.” What kind of conversation could I have with an electronic verifier? I turned to fiction, to breathe a narrative into the static image.

What better way to understand a love note verified by a fictional entity than to ask a fictional love story? What better love story could I use than Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, where the main characters move through a world where love is shaped by absence, where the body is a question, not an answer. Their story mirrors the tension I confront: an anonymous radiologist who sees inside my daughter but never meets her. In an age when AI writes condolence letters and diagnoses arrive preceded by push notifications, Kundera’s exploration of the soul-body split works. To decode this strange and clinical love note, I must fragment it and search for meaning in the space between scan lines.

The medical imaging artifact serves as a fragment of my daughter, a sliver of her rendered in code, replacing the kind of information that, in the past, her physical body would have provided the physician or, perhaps, hidden from him.

The scan or record is often alien to the patient. It is alien: a cryptic portrait without a face. That was then; this is now. Artificial intelligence ups the ante. Cardiologist and digital health scholar Eric Topol warns that as artificial intelligence increasingly mediate diagnosis and treatment, what is wrong with health care “won’t be fixed by advanced technology, algorithms, or machines” (4). We need human intervention.

That night in the ER occurred when radiologists still held the final word and the machines did not speak so loudly. But now, in the age of algorithmic triage and AI-generated empathy, the image feels even more distant and layered, flattened, interpreted by systems trained to see patterns. So I turn to fiction, because only fiction knows how to hold both the body and its metaphor, to make meaning where medicine leaves silence.

When we fragment the clinical text that interprets the image—split lit it open and let it bleed--we create new ways of understanding both the physician and the cold poetry of the medical report. Fragmenting the text-based interpretation of the image creates a new way of understanding the physician and the cold poetry of the medical report.

It offers something like Barthes and the Surrealists’ out-of-context analysis of images and written texts as explained by Robert Ray: “Both Barthes’s ‘third meaning’ practice of reading movie stills and the Surrealist strategies of film watching amount to methods of extraction, fragmentation” (36). In S/Z, Barthes provides an exhaustive appraisal of how readers generate that meaning. He isolates detail from the narrative, so that its meaning becomes open for new interpretation. In this case, we rearrange the fragments of science and fiction to reveal what they can tell us about the physician/patient relationship, my daughter, myself, and more.

The tearing and fragmentation process mimics how the radiologist fragmented my daughter to understand her pathology. He penetrated her with his gaze, though from afar, and exposed her “Frontal and lateral views of the chest,” leaving the rest of her untouched by anything but traces of radioactivity and by the invisible compression algorithm that turned her flesh into JPEG artifacts for cloud storage.

Betty Kevles points out that from the x-ray to the digital images produced by more sophisticated imaging technologies, such as CT, MRI, and PET, visual medical technologies have “increased the sense of fragmentation that comes from seeing parts of our inner selves as transitory patterns on video monitors” and focused on specific organs, similar to the move from general practitioners to specialists focusing on body part” (261-262). Today those ‘transitory patterns’ are triaged first by anomaly-detection AI before a human ever scrolls past them. Fragmentation. By isolating and dislocating, it is possible to create.

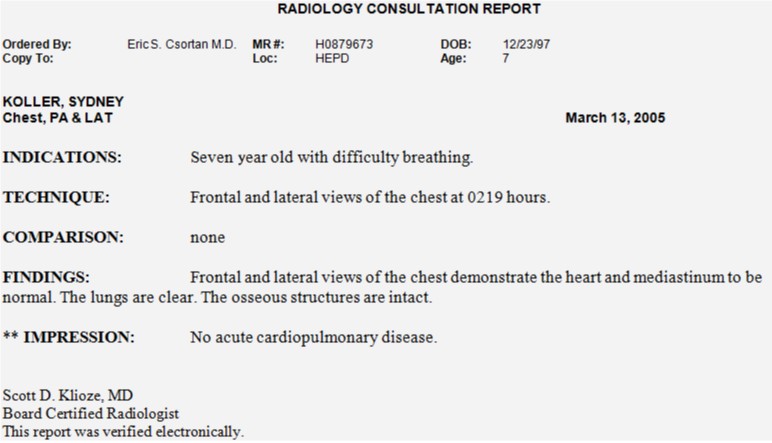

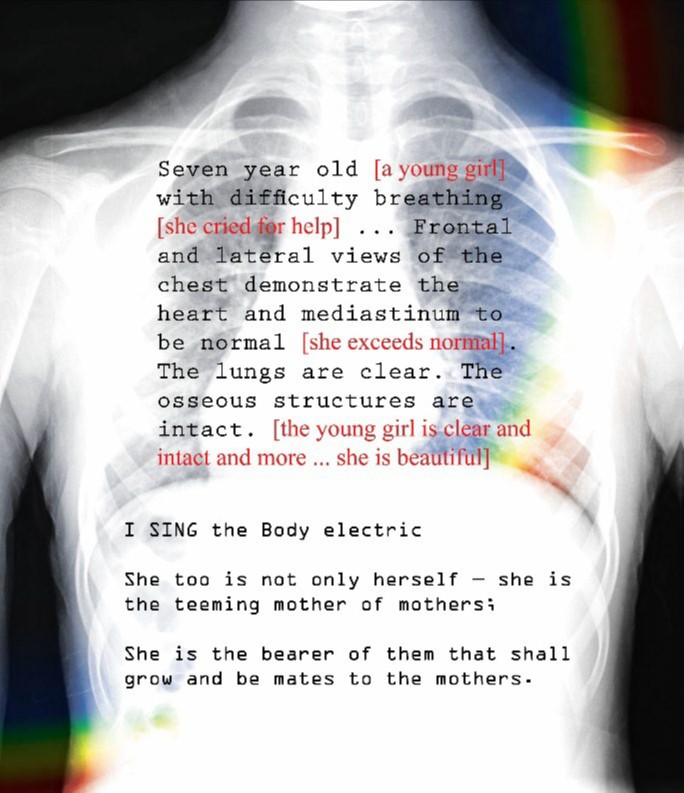

As an aside, I created a collage of texts from fragments of the x-ray, radiological report, a Whitman poem, and my own voice, where these fragments pulled from an infinite web of texts come together in a collage to speak to give me a new understanding of my daughter. The image becomes a doorway to a discourse of tangents.

Marcel O’Gorman justifies the use of language tricks to make “unconventional, yet informative, linkages between concepts” (12). Gorman argues that images and texts may be used “as an inlet onto a network of discourses” (22) and linguistic gyrations such as punning can be used as a research tool.

As a baby, my daughter’s first words were no and dada, so it seems to make perfect sense now that Sydney was saying no to the Dada movement, and instead instructing me to look beyond at an offspring of Dada – surrealism. The Surrealists practiced cut-up and collage wherein text is rearranged to understand each fragment and the reconstituted whole in a different way.

I refuse to slip into the unconsciousness of surrealism, however, and will search with intent to find the right fragments, the right language. I want to use the imaging report and love story as a lens for seeing things more clearly or, according to O’Gorman in his explication of picture theory, “as a generator of concepts and linkages unavailable to conventional scholarly practices” (12).

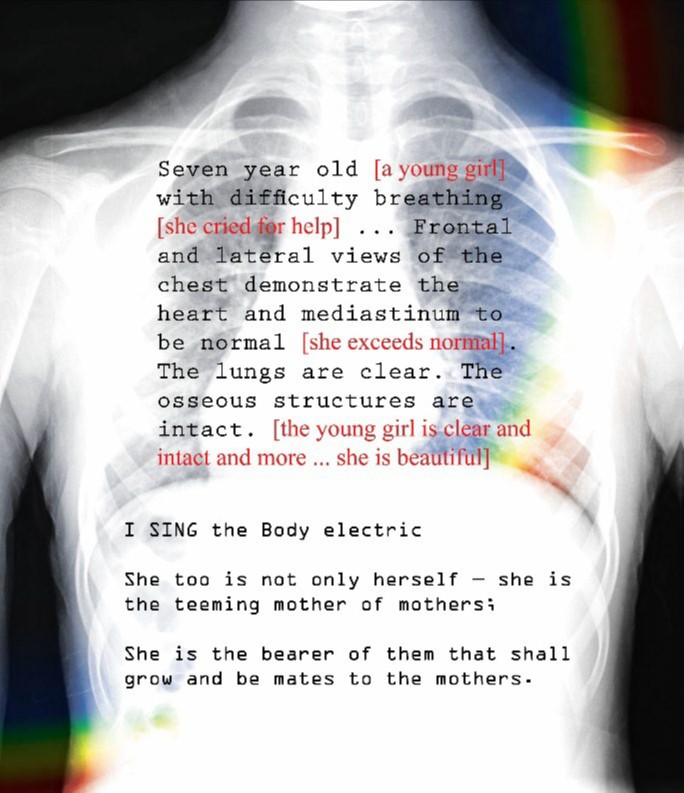

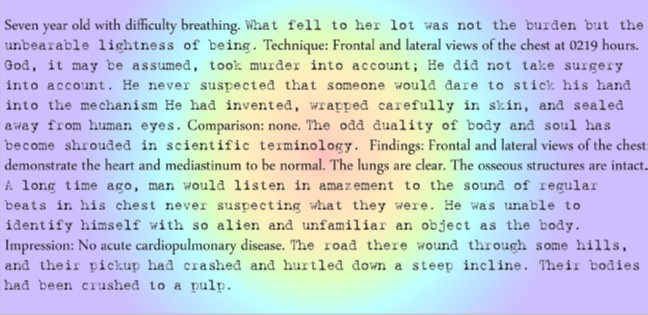

Fragmenting the medical record of the x-ray itself gives me a way of understanding Sydney’s radiologist, the cryptic medical report, my daughter’s own body then and 20 years later, and the rest of humankind. It isolates the detail from the narrative so that its meaning becomes open for new interpretation. In this case, I rearrange the fragments with fragments from The Unbearable Lightness of Being to produce new information. See image 3. The textual voices are distinguished by different typefaces.

By searching through the Kundera novel, I filled in the blanks of the radiologist’s love note; I decoded the white space and completed the communication between the electronic verifier and my daughter. This juxtaposition of the love note and love story offers a way of addressing the puzzle of meaning in this ostensibly medical interaction.

What questions does this conversation between medicine/science and literature/fiction answer? It’s clear: “Seven year old with difficulty breathing. What fell to her lot was not the burden but the unbearable lightness of being.” What fell to my young daughter’s lot that night was not the burden of illness, croup, or of lack of breath; it was the agonizing pain of living in a body that requires breath. The love note hints at it. Her lightness – the lightness of childhood, innocence, and maybe my love – became unbearable for her that night. As she coughed spasmodically and screamed that she couldn’t stop, she felt the pain of existence and the fear that it would be snatched from her.

We see from the text that God had no idea; the technique was ungodly. “Technique: Frontal and lateral views of the chest at 0219 hours.” Two-nineteen refers to the two of us, Sydney and I, waiting as one billing unit (for hospital purposes), at one moment in time when we were not dressed to the nines. This is significant. Our clothing was our own.

God, it may be assumed, took murder into account; He did not take surgery into account. He never suspected that someone would dare to stick his hand into the mechanism He had invented, wrapped carefully in skin, and sealed away from human eyes.

God therefore could not have envisioned the x-rays that penetrated Sydney’s skin with a mysterious, invisible ray that produces – like murder – both dangerous and thrilling results: the exposure to radiation and the spectacular artifact created by that radiation.

“Comparison: none. The odd duality of body and soul has become shrouded in scientific terminology.” As the new text states, there is no comparison. The duality between body and soul, between my daughter as female, patient, child, and her radiologist as male, physician, adult becomes more apparent. But wait! His love for her is becoming suspect.

“Findings: Frontal and lateral views of the chest demonstrate the heart and mediastinum to be normal,” How could he call her “normal,” especially her heart? While normality is historically the ideal condition of a patient, it’s a sham that keeps us in a constant state of pathology. As a person he loves, what could such a banal description of my daughter mean? You cannot love someone who has a “normal” heart. It’s insulting. Love requires exceptionality. But things appear to improve; the explanation follows. We see that “scientific terminology” shrouds the truth. Moving along, we learn through an interpretation of the x-ray image that my daughter’s lungs are clear and her bony structures intact, but we are reminded that things were not always as they are:

A long time ago, before smartwatches buzzed to signal them, man would listen in amazement to the sound of regular beats in his chest never suspecting what they were. He was unable to identify himself with so alien and unfamiliar an object as the body.

The love story reminds us of a time when we romanced the body and were romanced by its ticks and murmurs, a time when our sounds remained mysterious rhythms that might have

emanated from the earth. The body, earth, sun, universe, God, and buttercups were all one conflated juggernaut. My daughter’s love mate seems to have grown impressed by my daughter. “Impression: No acute cardiopulmonary disease.” Thank God. But, reading on, we learn that: “The road there wound through some hills, and their pickup had crashed and hurtled down a steep incline. Their bodies had been crushed to a pulp.” What is this winding road and how can I stop my daughter from getting in the pickup before it’s too late?! The road cannot be life; that’s far too easy a metaphor. Is the road one day – the day of all days – when no matter how “normal” her heart and mediastinum, they will fail her and she will be crushed to a pulp? Her breath extinguished? I need to know who rides with her, whether the radiologist sits there, a new lover, God, or maybe it’s me. This says that despite all of her radiologist’s efforts at seeing inside of her and no matter how she exposes herself to his gaze in an effort to endure her lightness of being, it is merely a prolongation of an inevitable outcome.

A year later, a physician visits our home and sees my daughter’s chest x-ray in a frame. I have shrunken and revised it in Photoshop. She’s mine, after all.

“It’s backwards,” he says. “The heart should be on the left.”

But how could he know her heart better than I do?

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Copyrighted by Author

Attribution must be given

Cannot be used for commercial purposes

No derivatives allowed

Endnotes

- Kevles, Bettyann. Naked to the Bone: Medical Imaging in the Twentieth Century. Basic Books, 1997.

- Kundera, Milan. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Translated by Michael Henry Heim, Harper & Row, 1984.

- O’Gorman, Marcel. E-Crit: Digital Media, Critical Theory, and the Humanities. University of Toronto Press, 2006.

- Ray, Robert. The Avant-Garde Meets Andy Hardy. Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Topol, Eric. Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again. Basic Books, 2019.

- Whitman, Walt. “I Sing the Body Electric.” Leaves of Grass, 1900. Bartleby.com, www.bartleby.com/142/19.html. Accessed 2 July 2025.

From Star Trek to Avatar, medical imaging in sci Fi seeps across the fiction/science blood brain barrier , a thinner line than the frenetic scrawling of an EKG readout. Nearly every medical scene in Sci-Fi eschews numerical data of real world modern medicine for the more cinematically impressing displays of ethereal specters of light hovering above the injured or Ill. Center stage of these scenes is the narrative's medical professional, whether Doctor or medic, who manipulates the glowing overlay of the imagined body or interfaces with a device that, in turn, interacts with the digitized patient.

An inner tension in these scenes stitched with the drama of the injured or Ill character exposes an elusive and covert concept: the inherency of fiction in science, which for this research transplants that drama from an explication of various sci Fi medical imaging scenes to the fictionalized reseeing and retelling of actual medical events, mythically, if not mystically, which with a more penetrating scan seems appropriate for understanding both real and fictionalized medical science. By using our own gaze to examine these complicated and real world medical events as they interlace fictionally, we can expose and lay bare the prose and prosody of medical imaging in science fiction, of the medico-fictional epistemological model.

Medical texts can be decoded with fiction; fiction generates knowledge. In a time when every device speaks—pinging, notifying, telling us what to watch, eat, buy—fiction offers relief from noise. Fiction gives shape to what the data excludes such as the pain and joy of human existence. Fiction offers truth.

I have a short, completely true story to tell. It is about a cryptic love note hidden in a radiology report that unravels the blurred boundaries between medical imaging, existential anxiety, and the stories we impose on clinical data in an age of algorithmic certainty that forgets how to read between the lines. To understand what the scan refused to explicitly state, fiction is conjured like a spell to summon meaning from the shadows, the metadata, and the margins.

If medical intervention feminizes the patient by establishing the physician as a patriarchal figure standing in authority over a passive, dutiful body, then it stands to reason that the relationship between the patient and physician must be one of love; it is the open, sacrificial love of a person offering herself on faith – in the medical credentialing process – to one who will make her whole.

My daughter’s lungs are 27 years old plus as of today. This story starts twenty years ago, one night when my daughter went to bed and began coughing. At midnight, I called her pediatrician.

“She can’t seem to breathe,” I said.

My daughter gasped for air; panicking made it worse. On her physician’s instructions, we went to the Emergency Room, where two kind medical staffers x-rayed her chest after the ER physician administered medication that stemmed her coughing fits. At the time, I registered them as men — and only now, decades later, do I realize I may have mistaken performance for identity. I share this detail with the understanding that memory, like medicine, is fragmentary and flawed.

The x-rays were to determine whether she had bronchitis or some other lung ailment. She didn’t. That night, the hospital experienced receiving a record number of head traumas from motorcycle accidents, moving croup patients down the list of priorities. My daughter and I spent hours in a cold room — no phones to distract us, no apps to diagnose her or conjure AI-generated calm from regurgitated fragments of data scraped from unimaginable sources. Instead, we watched videos of dancing bears on a very small television set. Nevertheless, she left the hospital able to breathe, which fulfilled our goal.

Later, I read the report interpreting my daughter’s x-rays and realized that the radiologist loved her. See image 1 for proof. Upon scrutiny, however, it seemed clear that he was hiding something, as lovers often do. The text – plainly a love note – that bonded my daughter and him, only covertly identified his feelings. I could not decipher his message very easily. His love remained hidden in a way that hurt me. The medical record seemed stripped of meaning; it said nothing of my daughter’s beauty, sense of humor, or love of domesticated animals.

My daughter was more than a “seven year old with difficulty breathing.” Yet I could not ask Dr. Klioze what he meant, because he only existed as a line of metadata. Neither my daughter nor I ever met Dr. Kloize. He appeared merely as a timestamp and sterile assurance that someone or something read the x-rays sometime later that night. The report itself states -- as an autobiography of sorts -- “This report was verified electronically.” What kind of conversation could I have with an electronic verifier? I turned to fiction, to breathe a narrative into the static image.

What better way to understand a love note verified by a fictional entity than to ask a fictional love story? What better love story could I use than Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, where the main characters move through a world where love is shaped by absence, where the body is a question, not an answer. Their story mirrors the tension I confront: an anonymous radiologist who sees inside my daughter but never meets her. In an age when AI writes condolence letters and diagnoses arrive preceded by push notifications, Kundera’s exploration of the soul-body split works. To decode this strange and clinical love note, I must fragment it and search for meaning in the space between scan lines.

The medical imaging artifact serves as a fragment of my daughter, a sliver of her rendered in code, replacing the kind of information that, in the past, her physical body would have provided the physician or, perhaps, hidden from him.

The scan or record is often alien to the patient. It is alien: a cryptic portrait without a face. That was then; this is now. Artificial intelligence ups the ante. Cardiologist and digital health scholar Eric Topol warns that as artificial intelligence increasingly mediate diagnosis and treatment, what is wrong with health care “won’t be fixed by advanced technology, algorithms, or machines” (4). We need human intervention.

That night in the ER occurred when radiologists still held the final word and the machines did not speak so loudly. But now, in the age of algorithmic triage and AI-generated empathy, the image feels even more distant and layered, flattened, interpreted by systems trained to see patterns. So I turn to fiction, because only fiction knows how to hold both the body and its metaphor, to make meaning where medicine leaves silence.

When we fragment the clinical text that interprets the image—split lit it open and let it bleed--we create new ways of understanding both the physician and the cold poetry of the medical report. Fragmenting the text-based interpretation of the image creates a new way of understanding the physician and the cold poetry of the medical report.

It offers something like Barthes and the Surrealists’ out-of-context analysis of images and written texts as explained by Robert Ray: “Both Barthes’s ‘third meaning’ practice of reading movie stills and the Surrealist strategies of film watching amount to methods of extraction, fragmentation” (36). In S/Z, Barthes provides an exhaustive appraisal of how readers generate that meaning. He isolates detail from the narrative, so that its meaning becomes open for new interpretation. In this case, we rearrange the fragments of science and fiction to reveal what they can tell us about the physician/patient relationship, my daughter, myself, and more.

The tearing and fragmentation process mimics how the radiologist fragmented my daughter to understand her pathology. He penetrated her with his gaze, though from afar, and exposed her “Frontal and lateral views of the chest,” leaving the rest of her untouched by anything but traces of radioactivity and by the invisible compression algorithm that turned her flesh into JPEG artifacts for cloud storage.

Betty Kevles points out that from the x-ray to the digital images produced by more sophisticated imaging technologies, such as CT, MRI, and PET, visual medical technologies have “increased the sense of fragmentation that comes from seeing parts of our inner selves as transitory patterns on video monitors” and focused on specific organs, similar to the move from general practitioners to specialists focusing on body part” (261-262). Today those ‘transitory patterns’ are triaged first by anomaly-detection AI before a human ever scrolls past them. Fragmentation. By isolating and dislocating, it is possible to create.

As an aside, I created a collage of texts from fragments of the x-ray, radiological report, a Whitman poem, and my own voice, where these fragments pulled from an infinite web of texts come together in a collage to speak to give me a new understanding of my daughter. The image becomes a doorway to a discourse of tangents.

Marcel O’Gorman justifies the use of language tricks to make “unconventional, yet informative, linkages between concepts” (12). Gorman argues that images and texts may be used “as an inlet onto a network of discourses” (22) and linguistic gyrations such as punning can be used as a research tool.

As a baby, my daughter’s first words were no and dada, so it seems to make perfect sense now that Sydney was saying no to the Dada movement, and instead instructing me to look beyond at an offspring of Dada – surrealism. The Surrealists practiced cut-up and collage wherein text is rearranged to understand each fragment and the reconstituted whole in a different way.

I refuse to slip into the unconsciousness of surrealism, however, and will search with intent to find the right fragments, the right language. I want to use the imaging report and love story as a lens for seeing things more clearly or, according to O’Gorman in his explication of picture theory, “as a generator of concepts and linkages unavailable to conventional scholarly practices” (12).

Fragmenting the medical record of the x-ray itself gives me a way of understanding Sydney’s radiologist, the cryptic medical report, my daughter’s own body then and 20 years later, and the rest of humankind. It isolates the detail from the narrative so that its meaning becomes open for new interpretation. In this case, I rearrange the fragments with fragments from The Unbearable Lightness of Being to produce new information. See image 3. The textual voices are distinguished by different typefaces.

By searching through the Kundera novel, I filled in the blanks of the radiologist’s love note; I decoded the white space and completed the communication between the electronic verifier and my daughter. This juxtaposition of the love note and love story offers a way of addressing the puzzle of meaning in this ostensibly medical interaction.

What questions does this conversation between medicine/science and literature/fiction answer? It’s clear: “Seven year old with difficulty breathing. What fell to her lot was not the burden but the unbearable lightness of being.” What fell to my young daughter’s lot that night was not the burden of illness, croup, or of lack of breath; it was the agonizing pain of living in a body that requires breath. The love note hints at it. Her lightness – the lightness of childhood, innocence, and maybe my love – became unbearable for her that night. As she coughed spasmodically and screamed that she couldn’t stop, she felt the pain of existence and the fear that it would be snatched from her.

We see from the text that God had no idea; the technique was ungodly. “Technique: Frontal and lateral views of the chest at 0219 hours.” Two-nineteen refers to the two of us, Sydney and I, waiting as one billing unit (for hospital purposes), at one moment in time when we were not dressed to the nines. This is significant. Our clothing was our own.

God, it may be assumed, took murder into account; He did not take surgery into account. He never suspected that someone would dare to stick his hand into the mechanism He had invented, wrapped carefully in skin, and sealed away from human eyes.

God therefore could not have envisioned the x-rays that penetrated Sydney’s skin with a mysterious, invisible ray that produces – like murder – both dangerous and thrilling results: the exposure to radiation and the spectacular artifact created by that radiation.

“Comparison: none. The odd duality of body and soul has become shrouded in scientific terminology.” As the new text states, there is no comparison. The duality between body and soul, between my daughter as female, patient, child, and her radiologist as male, physician, adult becomes more apparent. But wait! His love for her is becoming suspect.

“Findings: Frontal and lateral views of the chest demonstrate the heart and mediastinum to be normal,” How could he call her “normal,” especially her heart? While normality is historically the ideal condition of a patient, it’s a sham that keeps us in a constant state of pathology. As a person he loves, what could such a banal description of my daughter mean? You cannot love someone who has a “normal” heart. It’s insulting. Love requires exceptionality. But things appear to improve; the explanation follows. We see that “scientific terminology” shrouds the truth. Moving along, we learn through an interpretation of the x-ray image that my daughter’s lungs are clear and her bony structures intact, but we are reminded that things were not always as they are:

A long time ago, before smartwatches buzzed to signal them, man would listen in amazement to the sound of regular beats in his chest never suspecting what they were. He was unable to identify himself with so alien and unfamiliar an object as the body.

The love story reminds us of a time when we romanced the body and were romanced by its ticks and murmurs, a time when our sounds remained mysterious rhythms that might have

emanated from the earth. The body, earth, sun, universe, God, and buttercups were all one conflated juggernaut. My daughter’s love mate seems to have grown impressed by my daughter. “Impression: No acute cardiopulmonary disease.” Thank God. But, reading on, we learn that: “The road there wound through some hills, and their pickup had crashed and hurtled down a steep incline. Their bodies had been crushed to a pulp.” What is this winding road and how can I stop my daughter from getting in the pickup before it’s too late?! The road cannot be life; that’s far too easy a metaphor. Is the road one day – the day of all days – when no matter how “normal” her heart and mediastinum, they will fail her and she will be crushed to a pulp? Her breath extinguished? I need to know who rides with her, whether the radiologist sits there, a new lover, God, or maybe it’s me. This says that despite all of her radiologist’s efforts at seeing inside of her and no matter how she exposes herself to his gaze in an effort to endure her lightness of being, it is merely a prolongation of an inevitable outcome.

A year later, a physician visits our home and sees my daughter’s chest x-ray in a frame. I have shrunken and revised it in Photoshop. She’s mine, after all.

“It’s backwards,” he says. “The heart should be on the left.”

But how could he know her heart better than I do?

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Copyrighted by Author

Attribution must be given

Cannot be used for commercial purposes

No derivatives allowed

Endnotes

- Kevles, Bettyann. Naked to the Bone: Medical Imaging in the Twentieth Century. Basic Books, 1997.

- Kundera, Milan. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Translated by Michael Henry Heim, Harper & Row, 1984.

- O’Gorman, Marcel. E-Crit: Digital Media, Critical Theory, and the Humanities. University of Toronto Press, 2006.

- Ray, Robert. The Avant-Garde Meets Andy Hardy. Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Topol, Eric. Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again. Basic Books, 2019.

- Whitman, Walt. “I Sing the Body Electric.” Leaves of Grass, 1900. Bartleby.com, www.bartleby.com/142/19.html. Accessed 2 July 2025.